|

|

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5 |

| Sample Essays |

6 |

A MUSICAL JOURNEY FROM MODE TO MODE

Nu’sach Ma’gen A’vot wanders musically between Minor and Major. Many composers, both cantorial and secular, have composed beautiful music built on this Nu’sach. Anton Rubinstein, a Russian Jewish composer who converted to Christianity, was considered musically more Russian than most of his Russian contemporary musicians. However, even having become almost totally assimilated, in the wonderful chorus melody of his famous opera “Demon, He could not “biologically” free himself from the Ma’gen A’vot Nu’sach… |

| |

|

| |

Nu’sach Kol Nid’rei is a musical journey from mode to mode, going from A’ha’va Ra’bah to Minor, and from Minor to Major, and back. The ending of this enchanting melody is totally in Major. It is therefore understandable why the great German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) fell in love with this sacred melody and immortalized it in one of his most monumental compositions, the String Quartet Number 14 in C Sharp minor. In its sixth movement, Adagio quasi un poco andante, the Viola clearly plays the Nu’sach of Kol Nid’rei over the background of the violins. |

| |

Excerpts from: The Jewish Minor, by Leib Glantz, 1961. |

| |

TOP |

| 7 |

THE ESSENCE OF CHA'ZA'NUT

In theory, the cantor improves and beautifies the prayer service, organizes the service, raises it to a level of Hit’la’ha’vut (enthusiasm), and to an enlightened musical level. Therefore, an analysis of cantorial must begin with the personal human attributes of the cantor. |

| |

|

| |

Cha’za’nut is not just a musical profession. It is not just a trade. It is wisdom (Choch’ma). Wisdom in all its aspects: Wisdom, understanding and knowledge. The integral mission assigned to the cantor consists of demands that are not necessarily musical. A cantor is undoubtedly a singer. However, a singer is definitely not a cantor, even when he performs cantorial in a synagogue. A classical soloist, highly respected by great conductors, can be a wonderful soloist, but he is not a cantor. The greatest Italian opera singer, in order to excel, is not required to be knowledgeable about the Italian people, their history, their customs and their culture. The cantor, on the other hand, must be a complete Jew in spirit and soul. He must be a scholar of Jewish history, ancient Jewish literature, the written and oral To’rah, the Ha’la’cha (interpretation of the laws of the Scriptures) and the Mid’ra’shim (Jewish commentaries on the Hebrew Scriptures). He must be familiar with the literature of the middle ages including its Pay’ta’nim (poets) and Pi’yu’tim (liturgical poems). He should be familiar with modern Hebrew literature. This Jewish consciousness is the primary basis for the wisdom of Cha’za’nut, and serves as the principle attribute of the cantor’s mission. |

| |

|

| |

A second attribute, one that is no less important, is the cantor’s standard of morality. Many singers and artists conduct their lives in what is often called “bohemian” lifestyle. They frequently indulge in alcohol and unrestrained social behavior. This kind of lifestyle does not disqualify the secular artist. Cantors, as leaders of their communities, are measured according to their morality. Their behavior must be a model for the public. A cantor is not just another member of the community, but an example of which to follow. His singing must originate from holiness and purity. |

| |

|

| |

A third important aspect of the Cha’zan is his credo (A’ni Ma’a’min). He must be loyal to his people and to their holy values. His religious faith must be unabridged, as he must believe in the words he is uttering, as he is required to be an interpreter of those texts. |

| |

Excerpt from: The Essence of Cha’za’nut, by Leib Glantz, 1958. |

| |

TOP |

| 8 |

A THOUGHT PROVOKING HOLIDAY

When I analyze the wonderful poem of Rabbi Amnon of Mayence -- U’Ne’ta’neh To’kef Ke’du’shat Ha’Yom (“We shall observe the mighty holiness of this day”), I become aware that it is free of begging for mercy. There is something more burning, more intense and more penetrating. In U’Ne’ta’neh To’kef we hear a poet’s artistic description and bold imagination of the Kingdom of the Heavens: “Thou unfoldest the records and the deeds therein inscribed that tell their story” (Ve’Tif’tach Et Se’fer Ha’Zich’ro’not U’Me’E’lav Yi’ka’reh.) |

| |

|

| |

This monumental poem stimulates me to call out to all the cantors and Jewish composers of our era and beg of them: Do not cry and do not lament on this glorious day of Rosh Ha’Sha’na! We have strayed far away from the penetrating philosophical ideas of the great philosophers of our past. It seems that our generation has chosen to simplify the meaning of our spiritual and cultural wealth to a primitive level that borders with ignorance! There is no need to shout or sob! After all, this is a festive day. The poetry of the prayers of Rosh Ha’Sha’na is glorious. The poets who wrote these poems employed thought and passion. Every word was a painting, a song, a philosophy. Sadly, many of us moan, sigh, flatter and plead as if we were beggars knocking on a door. |

| |

Excerpt from: Rosh Ha’Sha’na – A Festive Day That Provokes Thought, by Leib Glantz, 1959. |

| |

TOP |

| |

|

|

| Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5 |

| |

|

|

|

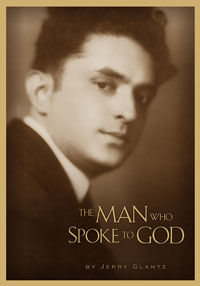

| Copyright © 2007, by Dr. Jerry Glantz |

|

|